It is now well known that the gut and immune system support one another to promote a healthy body: Our gut health plays a crucial role in supporting healthy immune responses.

So how are these connected and how does the health of our gut lining and our microbiome effect our immune system?

Firstly, lets’ take a look at the function of our immune system.

Immune System: Basic Functions

Your immune system plays a vital role in the body and is designed to protect it from foreign and harmful invaders.

It consists of a group of cells, proteins and organs that work together to protect the body from germs, viruses, fungi, pathogens and toxins found in our food, air, water and beauty/cleaning products. Immune cells act as your body’s first line of defence – they recognise, identify and neutralise any harmful substances (environmental or pathogenic) that have found their way into the body.

When the immune system is working optimally, it goes unnoticed. However, when it doesn’t work adequately or when you are run down, your defences become too weak to fight. Opportunistic and bacteria and viruses swoop in and are more likely to make you ill.

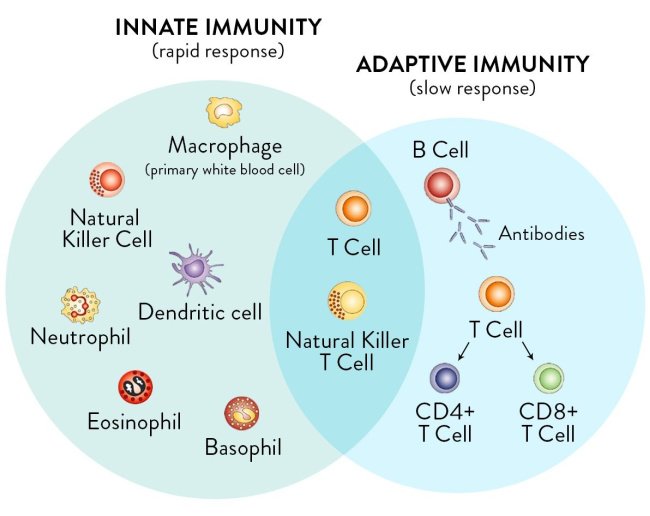

The immune system is made up of two subsystems– the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system.

The innate immune system defends the body from non-specific pathogens that enter the body. It acts primarily through immune cells called killer cells and phagocytes (eating or engulfing cells which fight pathogens that enter your body through various passageways (mouth, skin and nose for instance).

The adaptive immune system targets particular pathogens already encountered by the body. It is also referred to as the acquired or specific immune response. The adaptive immune system, as the name suggests, adapts to changes in the strains of bacteria and viruses so that it learns to defend the body even over time.

How does our immune system get activated?

When our body doesn’t recognise something as our own, the immune system gets into gear, ready to fight back.

We refer to the ‘attackers’ of the immune system as antigens. Some of them are proteins found on the surface of viruses, bacteria and fungi. The way this works is as they enter the body and bind to immune cell receptors, this activates a sequence of events.

Immune cells have the powerful capacity to remember germs they encounter. Once an antigen has been identified, they record its information and the way to neutralise it for future reference. That way, next time the germ reappears, immune cells will know how to fight it more effectively.

The only problem that arises is when the immune system is weak or misfunctioning, it confuses our own healthy body cells with antigens. A ‘leaky gut’ can lead to unwanted substances being absorbed and coming into contact with our gut-associated lymphatic (immune) tissue. You can find out more about ‘leaky gut’ in my article here.

The body’s cells also contain proteins on their surface. When it is working properly, these proteins should not prompt an immune response against our cells. But in autoimmune disease, the immune cells wrongly think that our own cells are foreign invaders or antigens – which is called an autoimmune response.

Now, to delve a little deeper, let’s take a look at our microbiome or gut bacteria

What is the Gut Microbiome?

Not long ago, we held the belief that bacteria had little to do with our well-being and considered it a separate entity that just assisted the digestion of certain foods. More recently, it has become a fact that humans possess as many bacterial cells as human cells – with over 10 000 species and trillions of microorganisms present in our gut!

The gut microbiome – which is a collection of bacteria that reside in the gut – has such widespread effects on the body, ranging from immunity, cognitive function, behaviour, appetite, metabolism, and digestive health (the list goes on).

It has been estimated that the human gut houses 100 trillion microbial cells (collectively referred to as the gut microbiota), which is 10 times the number of human cells. So we are effectively more bacteria than we are human.

The question is – how do our human cells interact with these microbes?

Over time, the body has evolved with bacteria in a symbiotic relationship. Human cells and bacteria live in close proximities and have a mutually advantageous relationship.

Researchers are only starting to see how large the influence of bacteria is on our health. In fact, the gut microbiota impacts many physiological processes. These include mood, level of concentration, memory, weight, digestion, and more.

Today, researchers are consistently pointing towards the influence of food on microbial composition and functioning. Some food allergens like soy, dairy and GMO corn can disturb the delicate intestinal lining of your gut while others like probiotics can support strengthening the tight junctions of the epithelial cells lining the gut. To find out more about the foods that affect our gut lining and how to treat leaky gut in my article here.

Maintaining a balanced ratio of good to bad bacteria is crucial for our health. The more good guys are on your side, the better chance your immune system and gut have a chance to protect the body the destructive bacteria.

The role of our gut bacteria and how it affects our immune system

The role of the immune system is to protect the body from illness and fend off unwanted pathogens and bacteria. But what about gut bacteria, how do these come into play?

The immune system is particularly interconnected with gut bacteria and the proper protective functioning of our gut lining.

As we know, most of the human microbiota resides in the gut, and as it turns out, so does 70-80% of the body’s immune system, referred to as GALT or gut associated lymphatic tissue. The relationship between the two is symbiotic whereby they have evolved together to ensure that the body is protected and is eliminating any harmful pathogens that it comes into contact with.

The interaction between the two begins at birth, which is the moment the body encounters bacteria for the first time –as the birth canal contains large numbers of bacteria. In time, the immune system forms the diversity of the microbiome and the gut influences the strength and development of the immune system. Throughout life, other factors also shape the composition of the gut flora, i.e. diet, environment, lifestyle habits.

The gut and the immune system support one another to promote a healthy body.

For instance, the gut microbiome acts as a gatekeeper and a trainer. It teaches immune cells called T-cells to distinguish foreign entities from our own tissue. When antibodies cannot access certain pathogens that have managed to attack our cells, T-cells mediate the situation and destroy infected cells – this process is referred to as cell-mediated immunity.

So the importance of maintaining a powerful immune system and proper communication with the gut is very clear.

When everything is running smoothly, the gut sends signals for the development of healthy immune function modulating immune responses. In exchange, the immune system helps to populate the microbiome with health-promoting microbes.

When these two are in good relations, the body is equipped to respond to pathogens and to tolerate harmless bacteria, preventing an autoimmune response and ensuring overall well-being.

Moreover, it has been well established that the abnormalities in the communication between intestinal bacteria and the immune cells can contribute to disease. Because the immune system is intricately related to the gut microbiota, if the body is exposed to bacteria-stripping factors (i.e. poor diet, antibiotics, surgeries, heavy metals, chemotherapy.), this lowers your intestinal flora, which can snowball into reduced immunity.

The intestinal lining of your gut is delicate, and when it is weakened, you are more vulnerable in the face of new harmful invaders. (Find out more in my article here). When your gut is out of balance, meaning not enough good friendly bacteria vs. the pathogenic, your whole body is affected.

Luckily, the same way bad guys can overpopulate the gut, good guys can too.

Improving your diet by cutting out processed foods and including more prebiotic fibre (vegetables and legumes) can increase biodiversity. Also, having probiotic-rich foods such as kefir, sauerkraut, and probiotics may restore the composition and reintroduce strong microbes, and supporting the vulnerable lining of the gut by including bone broth in your diet will also allowing for a more efficient gut microbiome, immunity and cognitive abilities.

If you are keen for more scientific based reading, check out these references

Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016 Aug 19;14(8):e1002533. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. eCollection 2016 Aug. PubMed PMID: 27541692; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4991899.

J. Qin, R. Li, J. Raes, M. Arumugam, K.S. Burgdorf, C. Manichanh, T. Nielsen, N. Pons, F. Levenez, T. Yamada, D.R. Mende, J. Li, J. Xu, S. Li, D. Li, J. Cao, B. Wang, H. Liang, H. Zheng, Y. Xie, J. Tap, P. Lepage, M. Bertalan, J.-M. Batto, T. Hansen, D. Le Paslier, A. Linneberg, H.B. Nielsen, E. Pelletier, P. Renault, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, K. Turner, H. Zhu, C. Yu, S. Li, M. Jian, Y. Zhou, Y. Li, X. Zhang, S. Li, N. Qin, H. Yang, J. Wang, S. Brunak, J. Doré, F. Guarner, K. Kristiansen, O. Pedersen, J. Parkhill, J. Weissenbach, MetaHIT Consortium, P. Bork, S.D. Ehrlich, J. Wang, A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08821

Hills RD Jr, Pontefract BA, Mishcon HR, Black CA, Sutton SC, Theberge CR.(2019) Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients. 2019 Jul 16;11(7). pii: E1613. doi: 10.3390/nu11071613. Review. PubMed PMID: 31315227;PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6682904.

InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); (2006). How does the immune system work? 2010 Nov 24 [Updated 2019 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279364/

Thaiss, C. A., Zmora, N., Levy, M., & Elinav, E. (2016). The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature, 535(7610), 65–74. doi:10.1038/nature18847

A.K. Abbas, A.H.H. Lichtman, S. Pillai, Cellular and Molecular Immunology E-Book, Elsevier Health Sciences, 2017.

Thaiss CA, Zmora N, Levy M, Elinav E. The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. 2016 Jul 7;535(7610):65-74. doi: 10.1038/nature18847. Review. PubMed PMID: 27383981.

Magrone T, Jirillo E. The interplay between the gut immune system and microbiota in health and disease: nutraceutical intervention for restoring intestinal homeostasis. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(7):1329-42. Review. PubMed PMID: 23151182.

Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, Pettersson S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012 Jun 8;336(6086):1262-7.doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. Epub 2012 Jun 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 22674330.

Hemarajata, P., & Versalovic, J. (2013). Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology, 6(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283X12459294